Women’s Health Exits Surpassed $100 Billion

From Forbes contributer, Geri Stengel:

On January 13, 2026, at the JPMorgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco, a new research report was released challenging one of healthcare investing’s most stubborn assumptions. Women’s health, long treated as a niche, has already produced more than $100 billion in acquisitions and IPOs between 2000 and 2025.

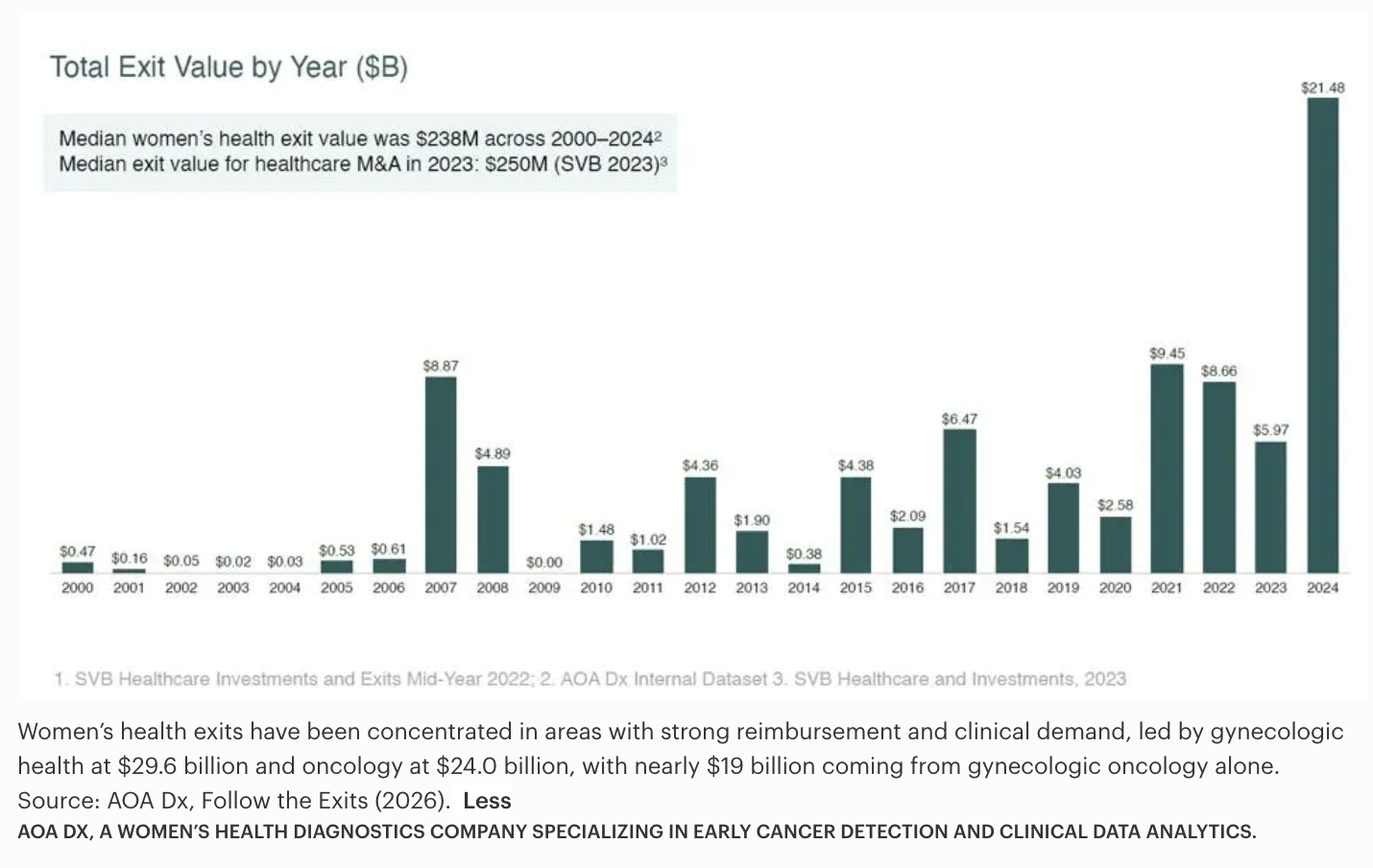

The research, Follow the Exits: Why Women’s Health Is a Smart Bet in Healthcare, documents 276 exits and 27 billion-dollar deals, including $27 billion in transactions in 2025 alone, the largest year on record for the category.

“What’s new isn’t momentum—it’s measurement,” Anna Jeter, co-founder of AOA Dx and lead author of the report explained in a Zoom interview. “We kept hearing from investors, ‘We’re just waiting for that first exit for women’s health to prove itself.’ And we were sitting there saying, ‘But we know this one, and this one, and this one—and they were billion-dollar exits.’”

Why These Exits Were Never Counted

Most women’s health companies were never labeled as women’s health in the databases investors use to track markets. They were classified as diagnostics, oncology, devices, or healthcare equipment, even when their products were designed specifically for women.

“When you look up these companies in PitchBook, they’re all segmented under equipment or diagnostics,” Jeter observed. “None of them are classified as women’s health.” That mislabeling matters. Investment platforms drive how capital is allocated. If exits are not tagged to a category, that category appears smaller, riskier, and less proven than it really is.

The problem is compounded by the FemTech label, which only appeared about five years ago and was never applied retroactively. “They are not going back and reclassifying what happened in the past,” Jeter remarked. “And because the tag is only five years old, you are not going to get many exits.”

The result is invisibility: Two decades of women’s health acquisitions and IPOs were recorded, but not counted as women’s health.

The $100 Billion Reality

When AOA manually rebuilt the dataset, the scale was impossible to ignore. Twenty-seven transactions exceeded $1 billion, and nearly half of all exits occurred in the past five years.

Jeter tested how well the industry understood those numbers. “I went around to a bunch of people I knew and asked how many women’s health unicorns there had been,” she described. “Everyone said ‘none.’ One person gave me one. When I told them it was twenty-seven, nobody knew.”

That gap between perception and reality has consequences. If investors believe a market is unproven, fewer deals get funded, fewer companies scale, and the category appears even smaller. Women’s health did not lack exits—it lacked visibility.

The same visibility gap that hid women’s health exits is now shaping who gets funded going forward. Institutional validation and algorithmic visibility—not consumer demand alone—are increasingly determining which women’s health companies are seen as investable. Innovative women’s health startups don’t have that visibility.

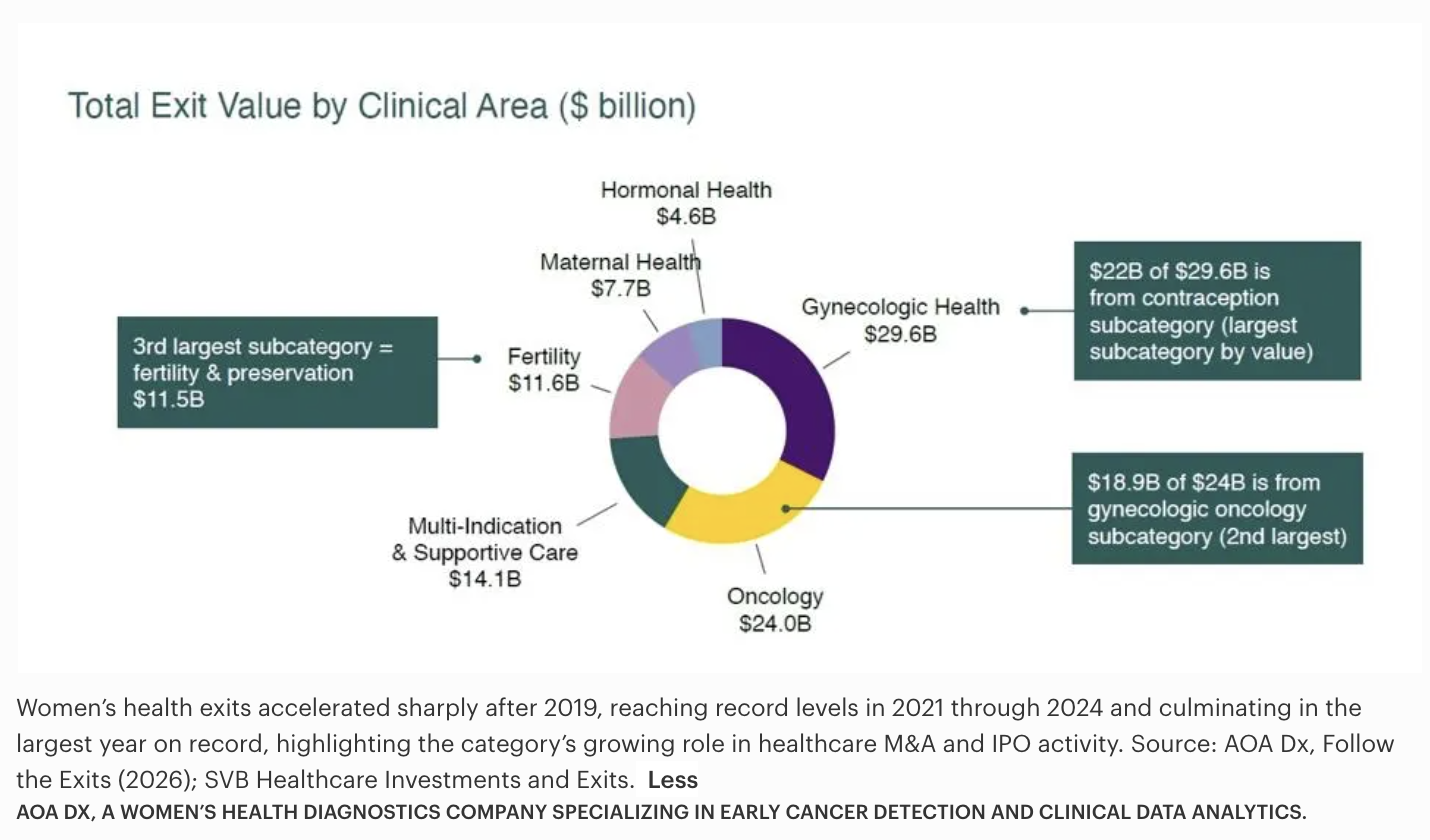

Diagnostics And M&A Drove Scale

The largest and most consistent women’s health exits came from diagnostics, especially cancer screening and molecular testing. “Two of the national cancer screening programs are women’s health—breast and cervical,” Jeter said. “These are huge things in our healthcare system that have been adopted for women by women.”

Those programs offer guaranteed reimbursement, high compliance, and steady demand, which is why strategic buyers continue to pay premiums for them.

Early detection also changes outcomes. In ovarian cancer, one of AOA’s focus areas, survival rates swing dramatically. “If you find ovarian cancer in stage one, you have a 92% five-year survival rate,” Jeter emphasized.

Women’s health also exits like mainstream healthcare. Ninety-one percent of exits were M&A, not IPOs. “That’s quite typical in healthcare,” Jeter shared. “It should give investors comfort that women’s health behaves like traditional healthcare.” Repeat acquirers, including Hologic, Roche, Labcorp, Abbott, and CooperSurgical, have built entire platforms through women’s health deals—a sign of sustained, not speculative, demand.

New data from global consultancy Kearney shows how narrow that capital lens still is. Since 2020, private investors have put $34 billion into women’s health, but nearly two-thirds of that—$21 billion—went into women-specific conditions such as fertility and women’s cancers, while just $13 billion flowed into conditions that disproportionately affect women, including cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, autoimmune disorders, and mental health.

Fertility and breast cancer alone captured about one-third of all private capital over that period, even as heart disease remains the leading cause of death among women, and Alzheimer’s disproportionately affects them. Kearney’s analysis tracked more than 2,000 private deals and found that diagnostics and digital health—two categories that have driven many of the largest women’s health exits—received only $7.6 billion in investment, highlighting a widening gap between where capital is being deployed and where value is being created.

That gap exists not because women’s health fails to exit, but because healthcare as a whole rewards a very specific kind of exit.

M&A have become the dominant exit strategy in healthcare, according to Silicon Valley Bank, because public markets remain difficult for emerging companies to access and scale, IPO windows are restrictive for most companies, and private equity has delivered a path to exit.

Strategic consolidation and PE “roll-ups” across provider services and technology businesses reflect a broader market preference for earlier, predictable exits over the uncertainty and cost of going public. This pattern aligns with industry dynamics in which regulatory, clinical, and commercialization hurdles make M&A a more efficient route, as it is often more economical for a large pharmaceutical buyer to acquire a drug candidate than to develop it internally.

Healthcare dealmaking has remained robust even as IPO activity lags, driven by such consolidation strategies that position smaller companies within larger platforms before they ever reach public markets.

The Next Billion-Dollar Markets

The most important shift is what now qualifies as women’s health. Menopause, Alzheimer’s disease, metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular disease are increasingly being examined through a sex-specific lens—opening large, undervalued markets.

“There is tremendous demand,” Jeter said. GLP-1 drugs are a case in point. They are marketed broadly, but more than 80% of users are women, creating opportunities for dosing, diagnostics, and care models designed for the primary patient population.

The same applies to Alzheimer’s and heart disease, where women are underdiagnosed, undertreated, and overrepresented among patients. Jeter hopes the report ends one idea once and for all. “The biggest misconception is that women’s health is a small market,” she said. “And that it is charity.”

The data released in Follows the Exits shows something else: Women’s health is already one of healthcare’s most proven exit markets—and one of its most undervalued.